This article was written by a member for the 30 May 1999 edition of the Way We Were In Woodsworth.

St. Lawrence was planned to be a neighbourhood unlike any other. And there was no other apartment building like Woodsworth in Toronto at the time it was built in 1979. “It wasn’t like any high-rise in Toronto,” according to Noreen Dunphy, who was the CHFT Development Coordinator. “It was a special place.”

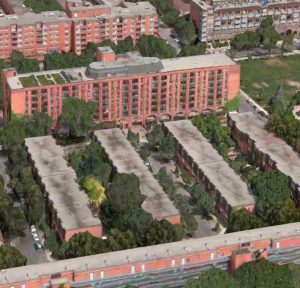

The City of Toronto purchased 44 acres of land and invited various stakeholders to join what became the St.Lawrence Neighbourhood committee. From the start, they imagined a mix of private and non-profit housing, with a significant mix of co-ops. The Cooperative Housing Federation of Toronto had a role in developing the whole layout of the neighbourhood: retail, mixed-use, the percentage of non-profit housing, the street design, and so on. The first phase of the St. Lawrence Neighbourhood extended from George St., Sherbourne Street and included the DB Archer, Woodsworth, Harmony and Cathedral Court co-ops and the Crombie Park apartments. It was 100% non-profit and had four-fifths co-ops. The second and third phases came some years later. After the St. Lawrence plan was developed, the city housing department got down to the job of allocating sites. CHFT was handed the Woodsworth site. The basic design was an apartment building on Wilton and townhouses in back.

However, the City and CHFT had somewhat different visions of Woodsworth. And the differences centred on issues of densities and cost versus building a sense of community. The city wanted to maximize density and wanted high-rise towers, 11 to 12 stories high. There were to be 200 to 220 units. “We didn’t like the feel of that”, says Noreen. “We wanted something on a more human scale.” CHFT wanted lower density and more “door on the street” units. It ended as a compromise. “We bargained with the city. We would pay a higher land price per unit.”

Woodsworth was a collaboration between Cooperative Housing Federation staff, who all lived in co-ops and architects. It was designed for the community from the very beginning.

How Woodsworth got its name

“I had the original planning role in the St Lawrence Neighbourhood development and then also Woodsworth. I was there from the beginning to the end”, Noreen recalls. And she came up with Woodsworth’s name. The first suggestion was Toronto Harbour Co-op. “But I didn’t want that. I wanted to call it after someone who would invoke the co-op spirit of service to others, that would reflect co-op ideas and values. I went to the Archives in the basement of City Hall and looked up the history of the site. I was looking for somebody great to commemorate. I wanted some connection to the Old Town of York (St. Lawrence Neighbourhood is located where the Old Town of York was founded).

The closest I came was a doctor who settled in the Old Town of York 200 years ago. There was a spot where the indigenous people lived, further back in the woods. But if they were going to travel down river and canoe Lake Ontario, one of their bartering spots was the base of the Don River and extended down to the St. Lawrence Market area. A doctor used to donate his time. He would come when they would camp to barter and fish, and he would provide his medical services. But I couldn’t find his name and couldn’t justify naming it after him.

We finally named it after Woodsworth, the founder of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation. He was a minister, believe fervently in social justice. While the leader of the CCF, he pushed for unemployment insurance, old-age pension and Medicare. “And that’s how Woodsworth got its name.”

Looking at history being unearthed

“In the two-story townhouses, we wanted to create a townhouse feel in that everybody had a door and an address on George and Frederick. Even the apartment on the top feels like a townhouse.

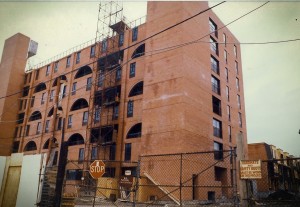

On Albert Franck, the water level beneath the street is high. “When first under construction,” remembers Noreen, “it was a sea of mud. Woodsworth is where the water was 120 years ago. It was an area of wharves and piers. We had to drive piles far into the ground to get a firm foundation. We were taking a site tour as they did this. They kept driving piles, and they kept disappearing into the muddy ground. They kept finding old rotting piers and wood. It was like we were looking at history being unearthed.”

“We wanted Woodsworth to feel different than any high-rise,” recalls Noreen. “We didn’t want people to feel alienated. We wanted to highlight the natural aspects of co-ops – breaking down barriers to neighbours knowing each other. It was not just a long dimly lit corridor where you hurry out of the elevator and lock yourself in the apartment.”

CHFT wanted to work cooperatively on the architecture. “We didn’t want an architect to go away, design a townhouse and fancy building and hand it back to us,” observes Noreen. She and CHFT staff spelled out a vision of a place of windows, light, community. The architects in turn tried to capture that sense. They showed them pictures of a fourteenth-century apartment building in Milan, Italy. “It was four stories high and had a “Galleria Approach” 120 years ago. But where Woodsworth’s arched windows are, it was an open-air arch.” In this ancient building, people would walk down corridors and chat with their neighbours in the sunlight. And this was the feel the architect was trying to create.

There were two rather unusual features architects used to convey this. One was a “single-loaded corridor,” a new concept for CHFT staff. It means apartment doors on one side only. This allows the other side to be all windows. The other feature is a “skip corridor”. You have a corridor on one floor and then skip. For instance, you have a corridor on the fifth floor, and then “skip” to the “sixth floor” where the two-bedroom units of the fifth floor are.

They designed with these two features for two reasons, says Noreen: “We wanted to offer as many units as we could with front and back windows. This lets in more light, more air. It just feels different. You can have a safer corridor, with more people travelling it. The one-bedrooms also let more light in from the corridor. The second floor can be bigger. The corridors can be wider. Also, it used indentations. It was not a straight smooth line down the corridor. It was brighter. Windows were allowed to open to give a sense of connection to the outside. So if you want to prop your door open for a few minutes and get some fresh air, you could. We wanted to give a sense of connection to the outdoors, light, kids playing.”

In the end, the architecture has helped to foster a sense of community and Woodsworth streets and corridors, and create a welcoming sight to come home to.